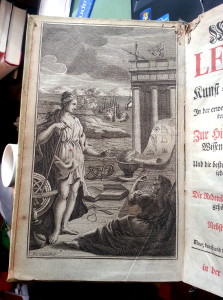

When I had my first computer with graphical capabilities (an Atari Mega ST) in 1986, I, like everybody else, started hacking fractals. Rather simple functions produced remarkably complex and unpredictable visualizations. It was clear, that there might be many more patterns and laws to be discovered in nature, as soon as we could enhance our minds and senses with the computer – structures and patterns way to subtle to be recognised with our unarmed eye. In that way, the computer became, what the microscope or the telescope hat been to the researchers at the dawn of modernity: an enhancement of our mind and senses.

“Number is an extension and separation of our most intimate and interrelating activity, our sense of touch” (McLuhan)

The origin of the word digital stems from digitus, Latin for the finger. Counting is to separate, to cluster and summarize – as Beda the Venerable did with his fingers when he coined the term digit. With the Net, human behavior became trackable in unprecedented totality. Our lives are becoming digitized, everything we do becomes quantified that is, put in quants.

With the first graphically capable computers, we could suddenly experience the irritating complexity of the fractals. Now we can put almost anything into our calculations – and we find patterns and laws everywhere.

What is quantified, can be fed into algorithms. Algorithms extend our mind into the realm of data. We are already used to algorithms recommending us merchandise, handling many services at home or in business, like supporting our driving a car by navigating us around traffic jams. With data based design and innovation processes, algorithms take part in shaping our things. Algorithms also start making ethical judgments – drones that decide autonomously on the taking or sparing the life of people, or – less dramatic but very effectiv though – financial services granting us a better or worse credit score. We have already mentioned “Posthuman Advertising” earlier.

The world is not only recognisable, the world in every detail is quantifiable. Our datarized word is the final victory of the Pythagoreans – all and everything to be expressed in mathematics. Data science in this way leads us to a similar revolution of mind, than that of the time of Copernicus, Galileo and Kepler.