The future of advertising after Siri – or: posthuman advertising.

by Benedikt Koehler and Joerg Blumtritt

The Skynet Funding Bill is passed. The system goes on-line August 4th, 1997. Human decisions are removed from strategic defense. Skynet begins to learn at a geometric rate. It becomes self-aware at 2:14 a.m. Eastern time. (Terminator 2: Judgment Day, 1991)

The advent of computers, and the subsequent accumulation of incalculable data has given rise to a new system of memory and thought parallel to your own. Humanity has underestimated the consequences of computerization. (Ghost in the Shell, 1996)

Are you a sentient being? – Who cares whether or not I am a sentient being. (ELIZA, 1966)

“Throughout human history, we have been dependent on machines to survive.” This famous punch-line from “The Matrix” summarizes what Canadian media philosopher Herbert Marshall McLuhan had brought to the mind of his time: Our technology as our culture cannot be separated from our physical nature. Technology is an extension of our body. Quite commonly quoted are his examples of wheels being an extension of our feet, clothes of our skin, or the microscope of our eyes. Consequently, McLuhan postulated, that electronic media would become extensions to our nervous system, our senses, our brain.

Advertising as we know it

Advertising means deliberately reaching consumers with messages. We as advertisers are used to sending an ad to be received through the senses of our “target group”. We chose adequate media – the word literally meaning “middle” or “means” – to increase the likelihood of our message to be viewed, read or listened to. After our targets would have been contacted in that way, we hope, that by a process called advertising psychology, their attitudes and finally actions would be changed in our favor – giving consumers a “reason why” they should purchase our products or services.

The whole process of advertising is obviously rather cumbersome and based on many contingencies. In fact, although hardly anyone would disagree in consumption as a necessary or even entertaining part of their lives, almost everyone is tired of the “data smog” as David Shenk calls it receiving between 5,000 and 15,000 advertising messages every day. Diminishing effectiveness and rising inefficiency is the consequence of our mature mass markets, cluttered with competing brands. Ad campaigns fighting for our attention ever more often can be experienced as SPAM. To get through, you have to out-shout the others, to be just more visible, more present in your target group’s life. The Medium is the Massage” as McLuhan himself twisted his own famous saying.

Enter Siri

When Apple launched the iPhone 4s, the OS had incorporated a peculiar piece of software, bearing the poetical name Siri (the Valkyrie of victory). At first sight, Siri just appears to be some versatile interface that allows controlling the device in a way much closer to natural communication. Siri has legendary ancestors, stemming from DARPA’s cognitive agents program. Software agents have been around for some time. Normally we experience them as recommendation engines in shop systems such as Amazon or Ebay, offering us items the agent would guess fitting our preferences by analyzing our previous behavior.

Such preference algorithms are part of a larger software and database concept, usually called agents or daemons in the UNIX context. Although there is no general definition, agents should to a certain extent be self-adapting to their environment and its changes, be able to react to real world or data events and interact with users. Thus agents may seem somewhat autonomous. Some fulfill monitoring or surveillance tasks, triggering actions after some constellation of inputs occurs, some are made for data mining, to recognize patterns in data, others predict users’ preferences and behavior such as shopping recommendation systems.

Siri is apparently a rather sophisticated personal agent that is monitoring not only the behavior on the phone but also many other data sources available through the device. You might e.g. tell Siri : “call me a cab!” – and the phone will autodial to the local taxi operator. Ever more often, people can be watched, standing at the corner, of some street muttering in their phones: “Siri, where am I?” And Siri will dutifully answer, deploying the phone’s GPS data.

Our personal Agents

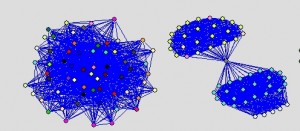

Agents like Siri are creating a form of representation of ourselves data-wise. These representations – we might also call them ‘avatars’ – are not arbitrarily shaped like the avatars we might take in playing multiuser games like World of Warcraft. It is not us willingly giving them shape but it is algorithms taking what information they might get about us to project us into their data-space. This is similar what big data companies like Google or Facebook do by collecting and analyzing our search inputs, our surfing behavior or our social graph. But in the case of personal agents, the image that is created from our data is kept in cohesion, stays somehow material, becoming even personally addressable. Thus these avatars become more and more simulacra of ourselves, projections of our bodily life into the data-sphere.

We hope the reader notices the fundamental difference between algorithms, predicting something about us from some date collected about us or generalized from others’ behavior like we find with advertising targeting or retail recommendations. In the case of our avatar, we really take the agent as a second skin, made from data.

And suddenly, advertising is no longer necessary to promote goods. Our avatar is notified of offerings and made proposals for sales. It can autonomously decide what it would find relevant or appropriate, just the way Google would decide in our place what web-page to rank higher or lower in our search results. Instead of getting our bodily senses’ attention for the ad’s message, the advertiser has now to fulfill the new task of persuading our avatar’s algorithms of the benefits of the good to be advertised for.

Instead of using advertising psychology, the science of getting into someone’s minds by using rhetoric, creation, media placements etc., will advertising will be hacking into our avatars’ algorithms. This will be very similar to today’s search engine optimization. Promoting new goods would be trying to get into the high ranks of as many avatars’ preferences as possible. Of course, continuous business would only be sustained, if the product would be judged satisfying by our avatar when taken into consideration.

A second skin

But why stop at retail? Our avataric agents will be doing much more for us – for the better or the worse. Apart from residual bursts of spontaneity that might lead us to do things at will – irrationally – our avatars could take over to organizing our day to day lives, make appointments for us, and navigate us through our business. It would pre-schedule dates for meetings with our peers according to our preferences and the contents of our communication it continuously monitors.

You could imagine our data-skin as some invisible aura, hovering around our physical body in an extra dimension. Like a telepathic extension of our senses, the avatars would make us aware of things not immediately present – like someone trying to reach out to us or something that would have to be done now. And although this might sound at first spooky, we are in fact not very far from these experiences: our social media timeline, the things we recognize in the posts of our friends and other people, we follow on Facebook, Twitter or Google+ already tend to connect us to others in a continuous and non-physical way. Just think of this combined with our personal assistants – like the calendars and notices we keep on our devices – and with the already quite advanced shop-agents on Amazon and other retailers – and we have arrived in an post-human age of advertising. This only requires one thing to be built before our avatar is complete: we need standardized APIs, interfaces that would suck the data of various sources into our avatar’s database. Thus every one of us would become a data kraken of our own. And this might be, what ‘post privacy’ is finally all about

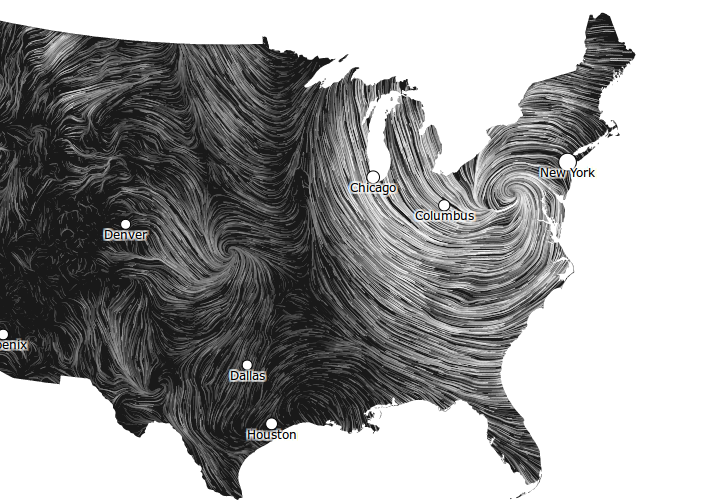

Open data is great. The National Digital Forecast Database offers free access to all the weather forecast data of the US National Weather Service. All of the US is covered with the predicted values for variables that influence the weather, like cloud cover, temperature, wind speed and direction.

Open data is great. The National Digital Forecast Database offers free access to all the weather forecast data of the US National Weather Service. All of the US is covered with the predicted values for variables that influence the weather, like cloud cover, temperature, wind speed and direction.